Freedom of speech isn’t a ‘trump card’ for Tornado Cash developers

Does code as freedom of speech mean that developers aren’t responsible for how their creations are used?

Crypto industry advocates are locked in a debate with regulators over whether a protocol’s code constitutes free speech, and what that means for liability.

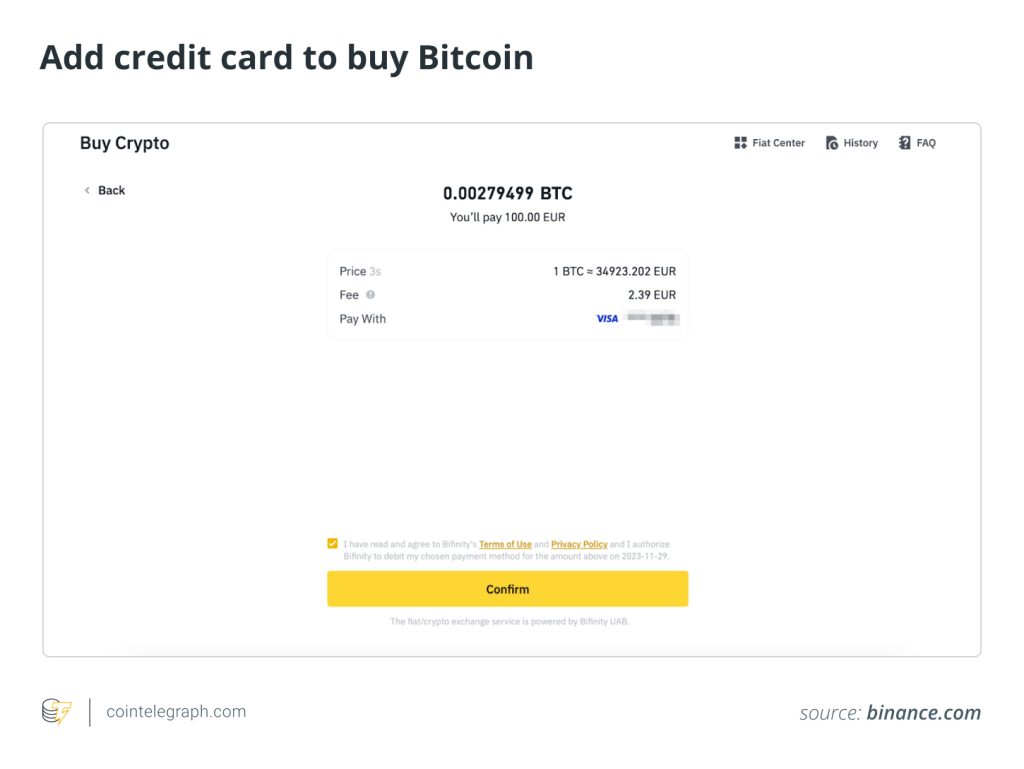

Lawmakers have long accused the crypto industry of facilitating illicit activities, from money laundering to financing terrorism. This has led to several court cases, arrests and even incarcerations.

Recent high-profile examples include the arrests of developers who worked on crypto mixers Tornado Cash and Samurai Wallet, as well as the United States Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SECs) planned enforcement action against decentralized exchange Uniswap.

The above cases have raised serious questions about whether developers are liable for what others do with their code. Some have gone so far as to call it an attack on free speech.

But is code really free speech? Or could some developers be abusing that definition to exempt themselves from liability?

While the crypto community believes that code-as-free-speech is a given, is that declaration true-to-life?

Legal precedent for code as free speech

In 1993, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) — a nonprofit organization defending civil liberties in the digital world — asked Cindy Cohn to serve as lead attorney in the Bernstein vs. Department of Justice case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

This case became crucial for code-as-free-speech advocates, as it ruled for the first time that software source code is speech protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Speaking with Cointelegraph, Cohn said that there are two polarized factions regarding the code-as-speech question.

On the one hand, some people think that because it’s code, it shouldn’t have special treatment and should be managed as a thing rather than speech. In Cohn’s opinion, this opinion resides mainly among government regulators.

On the other hand, some people think that once code is established as free speech, the government must be completely hands-off and have no power to regulate its use — a belief held by many in the crypto community.

But Cohn noted there is further consensus in the crypto industry that code is not just free speech but should offer immunity:

“Crypto enthusiasts want to think of freedom of speech in code as a trump card as if you’re throwing down the joker and you win.”

“Neither of these groups is right,” Cohn added.

So what defines the boundaries of code as free speech, and are crypto advocates wrongly claiming protection?

When should freedom of speech protect code?

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution forbids Congress from making any law that could limit the free expression of religion, press, assembly or speech.

For Cohn, the First Amendment is a potent instrument “to protect innovation, science, art, ability to communicate and finally to develop a democracy.” In the case of writing code, Cohn described it as just another form of expression: “It’s just a language in which people can express scientific ideas to each other.”

The development of blockchains and cryptocurrencies involves lots of math and science. Therefore, Cohn said that the sector’s development will be protected by speech, noting that “the First Amendment has a special concern for protecting that kind of inquiry.”

Recent: Real-word asset tokens can stabilize DeFi — Market observers

Additionally, within the crypto community, there is a tendency to develop open-source code, which aims to provide more academic and scientific value to the code as it is developed collaboratively and transparently.

Nevertheless, Cohn clarified that open-source code alone does not guarantee protection under the First Amendment; rather, the creator’s intention is key.

If the developer creates code exclusively to make money off of breaking the law, freedom of speech cannot be invoked.

Cohn stressed that if the code has both positive and negative use cases, then the code’s creator should not be held responsible for the bad uses of their creation.

However, Cohn said that many crypto projects claim to have a positive use case that no one actually uses, with developers adding some “frosting” to their product to cover up the illicit use cases.

She noted that a court would “rightfully claim the project is dressing up” their harmful use case and won’t accept a freedom-of-speech defense as there is a clear malicious intent.

Regulators could be scaring off scientific development

With cases such as Tornado Cash, Samourai Wallet or Uniswap, regulators may have scared off legitimate open-source projects.

According to Cohn, regulator actions against crypto developers, namely those involved in Tornado Cash, have had an unnecessary and “tremendous chilling effect.”

She said that regulators need to “create a space where people feel safe to participate in these collaborative projects,” adding:

“The government isn’t supposed to scare you out of writing something specific or academic; society is better off when people are able to develop scientific ideas.”

For Cohn, going after developers is like “prosecuting the hammer because somebody used it to hit someone over the head. The hammer isn’t the bad thing; it’s the use of the hammer.”

Still, financial regulators like the SEC have the power to curtail certain types of speech, and rightly so. Cohn cited the example of insider trading.

However, the latest cases in the crypto sector seem to show how “they’re extending their tentacles into kind of a more traditional academic and scientific inquiry,” Cohn added.

Cohn believes that laws around speech must be narrowly tailored to avoid working out of scope. Narrow tailoring refers to the legal principle where a law or regulation is specifically crafted to address a particular issue or achieve a specific goal without unnecessarily burdening or infringing upon other rights or interests.

She said Tornado Cash was one example of regulators’ failure to narrowly tailor the law. The aim was to tackle illegal transactions from North Korean hackers, but the broader effects were the arrest of developers, the suspension of GitHub accounts and the removal of the code of the mixer.

Effects of placing code as speech at risk

This has had consequences beyond the cryptocurrency space.

Matthew Green, a cryptography professor at Johns Hopkins University, wrote in a tornado-repositories repo on GitHub how the code removal interrupted his academic use of the Tornado Cash open-source code.

Green said he made “extensive use of the Tornado Cash and Tornado Nova source code to teach concepts related to cryptocurrency privacy and zero-knowledge technology.”

He further stated that the code removal was detrimental to academic exploration in this field, as the “loss or decreased availability of this source code will be harmful to the scientific and technical communities.”

Another immediate effect of regulators targeting developers is uncertainty.

Bundeep Singh Rangar, a venture capitalist and CEO of digital asset firm Fineqia, told Cointelegraph that “such legal actions introduce uncertainties that can affect investor confidence.”

Subsequentially, “If legal pressures on developers intensify, it could deter investment in U.S.-based tech companies as investors become wary of potential regulatory hurdles.”

In his opinion, “when developers face legal repercussions for their code, it can threaten the fundamental freedoms that drive our industry forward,“ which could eventually “stifle innovation.”

Rangar said that while the United States generally fosters creativity and exploration, “investors might seek out jurisdictions with clearer regulatory frameworks to avoid uncertainties surrounding developer freedoms.”

While Bernstein vs. Department of Justice established code as free speech, Cohn warned that the “law is fluid” and, therefore, its status can change.

Recent: Tornado Cash verdict has chilling implications for crypto industry

She added that many regulators think that “killing an open source project” and scaring off developers is “just irrelevant because they’re going after securities fraud, and so it doesn’t matter at all — they’re not right either.”

Cohn believes one of the key things that a court should look into is “evaluating whether the First Amendment is being met or abused by what an agency does,” as well as their collateral effects.

She said the courts will primarily consider the fit between regulators’ actions and goals. Therefore, when a regulator takes action on a speech-related subject, it needs to justify itself.

The ongoing cases of Tornado Cash, Samourai Wallet and Uniswap will become a battleground where the new boundaries of freedom of speech on code are tested.

Responses