How to mine Ethereum: A beginner’s guide to ETH mining

What is Ethereum mining?

Cryptocurrency mining is a process of solving complex mathematical problems. Miners are essentially the cornerstone of many cryptocurrency networks as they spend their time and computing power to solve those math problems, providing a so-called “proof-of-work” for the network, which verifies Ether (ETH) transactions. Ethereum, like Bitcoin (BTC), uses a proof-of-work (PoW) consensus process at the moment and will soon switch to a proof-of stake (PoS) mechanism.

Besides that, miners are responsible for creating new Ether tokens through this process, as they receive rewards in Ether for successfully completing a PoW task.

PoW relies on fundamental properties of the hash function, an “encrypted” piece of data that is procedurally derived from some arbitrary input. The difference between hashes and standard encryption is that the process only goes one way.

The only meaningful way to find what input was used to generate a given hash is to try to hash all possible input combinations and see which one fits. This is further complicated by the fact that tiny alterations in initial data will produce completely different results.

Proof-of-work starts by designating a list of desired hashes based on the “difficulty” parameter. Miners must brute force a combination of parameters, including the previous block’s hash, to create a hash that satisfies the conditions imposed by difficulty. This is an energy-intensive task that can be easily regulated by turning difficulty higher or lower.

Miners have a certain “hash rate” that defines how many combinations they try in one second, and the more miners participate, the harder it is to replicate the network for outside entities. By putting real work in, miners secure the network.

This article will guide you on how to mine Ethereum? How Ethereum transactions are mined? How does ethereum mining work?

Why should you mine Ethereum?

Mining turns the act of securing a network into a complex but usually quite profitable business, so the primary motivation for mining is making money. Miners receive a certain reward for each block, plus any transaction fees paid by users. Fees generally make a small contribution to overall revenue, though the decentralized finance boom in 2020 helped change that equation for Ethereum.

There are other reasons why someone would want to mine Ethereum. An altruistic community member could decide to mine at a loss just to contribute to securing the network, as every additional hash counts. Mining can also be useful to acquire Ether without having to directly invest in the asset.

An unconventional use for home mining is a form of cheaper heating. Mining devices turn electricity into cryptocurrency and heat — even if the cryptocurrency is worth less than the cost of energy, the heat on its own could be useful for people living in colder climates.

Will the proof-of-stake transition kill Ether mining?

A common concern for any prospective Ethereum miner is the Ethereum 2.0 roadmap, which introduced plans to transition to proof-of-stake, a consensus algorithm that would deprecate miners where all existing Ethereum miners have limited time available to earn a return on their investment. But thankfully, PoW mining is likely to be still functional until about 2023.

The Ethereum 2.0 Phase 0 launch, expected for 2020, is a separate blockchain that will not impact mining in any way. It’s only with Phase 2 where mining may begin to be deprecated, but there are no concrete plans for that transition as of October 2020.

Phase 2 is expected to come around the end of 2021 or early 2022. But it’s worth pointing out that Ethereum has a long history of delays with its roadmap — in 2017–2018, it was widely believed that the transition would be completed by around 2020. Nobody truly knows when Ethereum 2.0 will be finished, but as of October 2020, most estimates suggest that new miners should have enough time to recoup at least a sizable portion of their investment into hardware.

ETH mining profitability: Is mining Ethereum profitable?

Whether any type of mining is profitable depends entirely on the cost of electricity in any given area. As a rule, anything below $0.12 per kilowatt consumed in an hour is likely to be profitable, though prices below $0.06 are recommended to make mining a truly viable economic enterprise.

These figures would disqualify most home mining attempts, especially in developed countries where electricity prices are generally above $0.20. Though it may be possible to turn a profit with such prices, the return on capital could be severely impacted. For example, a miner that costs $3,000 generates $200 per month in revenue and that uses $45 in electricity at $0.05/kWh will take 19 months to repay itself. The same miner used in an area where electricity costs $0.20/KWh will be repaid in 150 months, or over 12 years.

Professional miners can gain an edge by moving their operations into regions with the cheapest electricity or by taking advantage of the generally lower rates reserved for industries. These are some of the primary reasons why mining has turned into a serious and capital-intensive industry.

But mining Ethereum at home is still accessible for most, especially since it can be done with consumer graphics cards made by AMD and Nvidia. For Ethereum miners living in regions with low electricity prices, it can also turn into a strong source of income.

A variety of ETH mining calculators exist that can outline what profits can be expected, for example, Miningbenchmark.net, Whattomine, or CryptoCompare’s calculator. It is also possible to calculate these values independently. The formula used by calculator websites is quite simple:

![]()

This provides an estimate of how much a miner is expected to make in a day. In essence, a miner’s revenue is the total issuance of the network multiplied by their share of the network’s total hash rate. To make a profit, one needs to subtract the cost of the electricity (i.e., the cost of Ethereum mining) used by the miner. For example, a device using 1.5 kWh of electricity at a price of $0.10 will cost $3.6 per day.

The values to plug into the revenue formula can be found online as well. Etherscan will provide an updated estimate of the total hash rate, as well as block times and block reward.

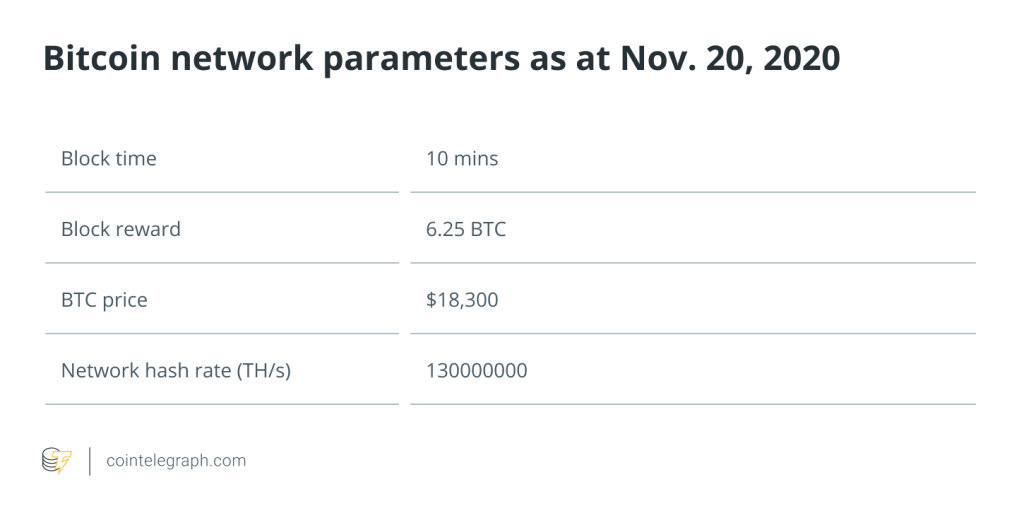

On the Ethereum network, current block times hold at 15 seconds, so there are 5,760 blocks in a day, and the reward is 2 ETH per block as of October 2020. The miner’s hash rate depends entirely on mining hardware, while the network hash rate is the sum total of all miners contributing to the network.

The key to successful mining is maximizing the hash rate while minimizing electricity and hardware costs. Therefore, in addition to location, the choice of mining hardware is crucial for mining.

How Ethereum transactions are mined?

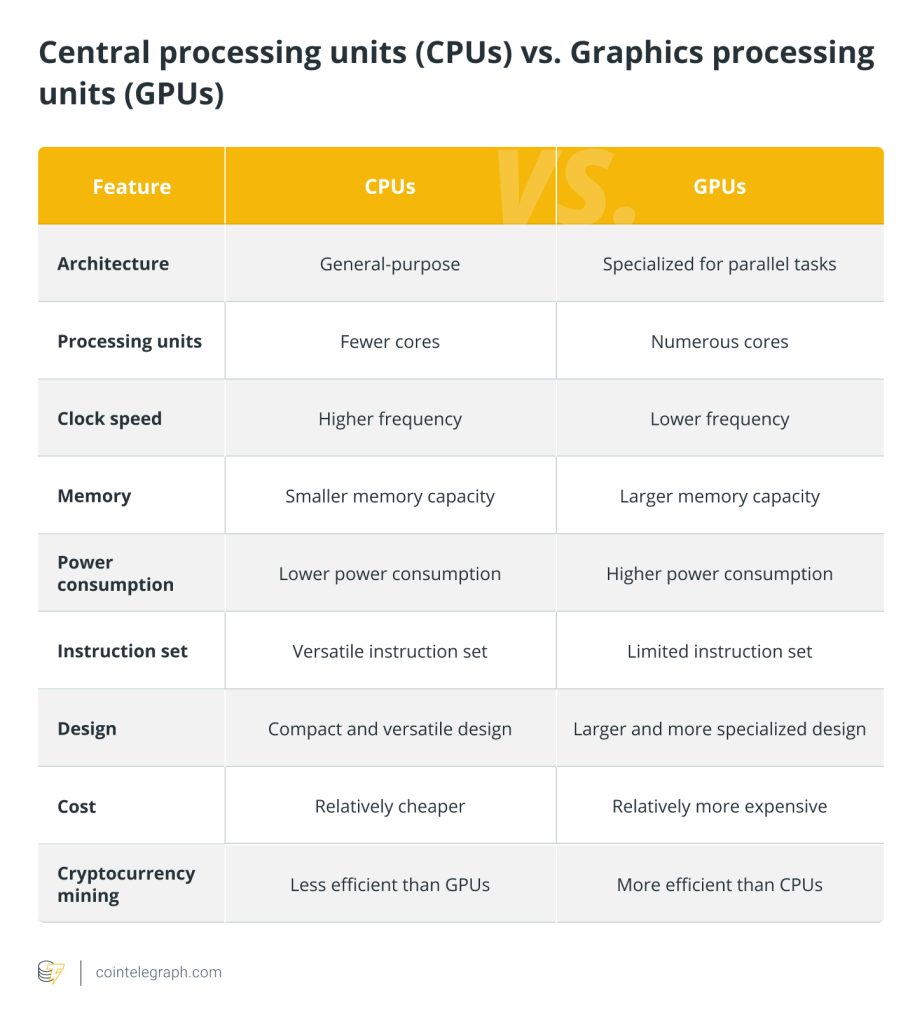

Ether was designed as a coin that could only be mined with consumer graphics processing units, or GPUs. This puts it in contrast with Bitcoin, which can only be mined effectively with specialized devices commonly referred to as application-specific integrated circuit machines, or ASICs. These devices are hardwired to only do one task, which allows them to achieve much higher efficiency than more generic computational hardware.

Making a mining algorithm that is “ASIC-resistant” is theoretically impossible and very hard in practice as well. ASICs designed for Ethereum’s mining algorithm, Ethash, were eventually released in 2018. However, these miners offer a relatively modest improvement over GPUs in terms of hashing efficiency. By contrast, ASICs for Bitcoin are substantially more efficient than GPUs due to the specifics of its mining algorithm.

Another type of specialized device is the FPGA, which stands for field-programmable gate array. These are a middle ground between ASICs and GPUs, allowing some form of configurability while still being more efficient than GPUs at particular types of computations.

It is feasible to mine Ethereum with all of these devices, but not all are practical or sensible. FPGAs, for example, are inferior to GPUs in most circumstances. They are expensive and very complex devices that require advanced technical knowledge to be used effectively. The reward is arguably not worthwhile, as their mining performance remains very close to that of leading GPUs.

Ether ASICs provide a measurable performance boost over graphics cards but carry a host of drawbacks in practical usage. The most important concern is that ASICs can only mine Ethereum and a few other coins based on the same hashing algorithm.

GPUs can mine many other coins and, if push comes to shove, can be resold to gamers or used to build a gaming PC. Additionally, ASICs are harder to source, as few shops sell them, while buying directly from manufacturers may require high order quantities and long waiting times.

So, for the hobbyist home miner, GPUs remain the most sensible choice due to their flexibility and relatively good performance compared to price.

How to find the best mining hardware?

Choosing the right hardware should primarily be dictated by three factors: its maximum possible hash rate, its energy consumption and its purchase price.

The purchase price is sometimes ignored, but it can make or break a mining operation, as hardware does not last forever. Component weardown is a factor, as eventually, all devices will fail. However, this issue is often overblown because GPUs are quite resilient devices, with many reports of them continuing mining for over five years.

The most significant risk affecting miners is hardware becoming obsolete. More advanced GPUs or ASICs can push out existing miners almost completely, especially those with higher electricity costs. Due to this, the “payback period” — how long it takes for the miner to pay itself back — becomes a very important metric for financial analysis in mining.

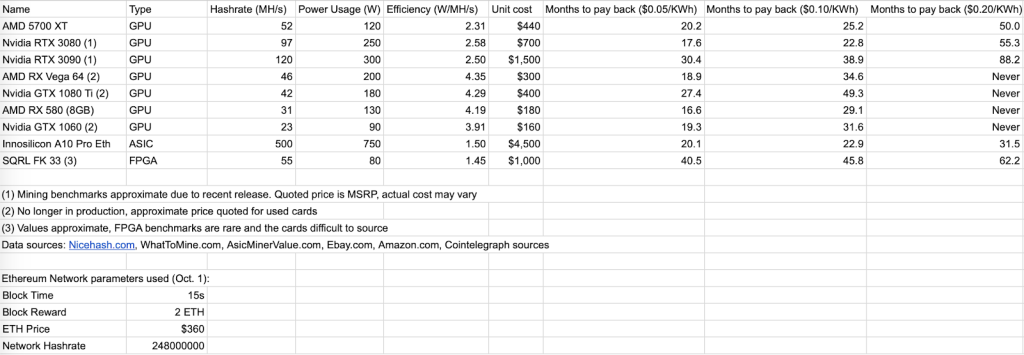

Below is a table listing the financial parameters of leading Ether mining hardware:

You can view and clone the spreadsheet to play around with the values.

The table analyzes the payback period where the lower the value, the better the result. This measure was chosen due to the large differences in hash rate among the devices, which would distort daily profit comparisons.

The calculations completely ignore any fees accrued, which are much more unpredictable than the block reward. Depending on the day, fees contributed 10%–50% of the total daily revenue in the summer of 2020, but historically, they hovered below 10%.

A further caveat is that this table was compiled in an advanced bull market. Some configurations are already failing to make money, and any drop in Ether’s price could exacerbate the situation. Overall, miner revenue fluctuates wildly, and extrapolations of one day’s proceeds into the future can be very unreliable. Miners compete for block rewards with one another, so lowering operating costs below the global average is the key to a resilient business.

Finally, the table ignores the cost of the remaining hardware required to assemble a miner. It is mostly a fixed cost and comparatively cheap, as GPU mining rigs use between six and 14 GPUs. ASICs are largely self-sufficient but, generally, require the purchase of external power supply units.

With those disclaimers in mind, the comparison nonetheless highlights a few differences and drawbacks of various mining hardware options. For example, a three-year old AMD RX 580 is the best value for your money at $0.05 per kWh. But its low energy efficiency makes it a much weaker option than others in the higher electricity cost brackets.

The A10 Pro ASIC is by far the most energy-efficient and attractive option for miners with high electricity costs. Other ASICs were not included due to extreme difficulty in purchasing or a short remaining lifespan. The Nvidia RTX 3080 is also an all-around strong alternative for every category of miners based on preliminary benchmarks.

The SQRL FK 33 is one of the more popular FPGAs, but this model highlights why this type of hardware sees little usage. Despite its high energy efficiency, its unit price still makes it unattractive compared to all the other options. However, it’s worth noting that the sample price figure was derived from the eBay listing of a refurbished second-hand device.

Buying used depreciated GPUs like the AMD RX Vega 64 or the Nvidia GTX 1060 can also be a good cost-saving measure, but buyers may run into a higher risk of device failures.

How does Ethereum mining works: Guidelines and risks

Mining requires careful planning and attention to avoid unfortunate outcomes. All computers are a potential fire hazard, and this risk is magnified in mining due to the constant usage and high energy outputs involved.

For in-home mining settings, it’s crucial not to overload the domestic electric grid with an excessive power draw. The grid as a whole and each single-socket are only rated for a certain maximum power, and mining devices can easily surpass those thresholds. The wiring could fail and overheat, posing an immediate fire hazard. Consult experts to evaluate the safety of your setup.

Choosing high-quality power supply units with ample power rating margin is highly recommended to protect from power surges and other electrical issues.

For GPU and FPGA mining rigs, there are several key hardware requirements for mining Ethereum effectively. Investing in specialized motherboards, such as the Asrock X370 Pro BTC+ or the Gigabyte GA-B250-FinTech, can be very worthwhile, as they are optimized for mining. Each motherboard may support up to 14 GPUs, which is normally impossible on standard motherboards.

The motherboard should be paired with a sufficient amount of RAM, 8 or 16 gigabytes, and at least 256GB of drive storage. The latter part is very important as Ethereum mining requires a lot of runtime memory, at least 4GB per GPU. Through an operating system trick called pagefile caching, this requirement can be offloaded to the much cheaper permanent storage with no performance loss. The GPU’s own RAM must also be at least 6GB to account for the growing DAG, a key mechanism of the Ethash algorithm.

The DAG, which stands for directed acyclic graph, is a large dataset used to compute the hashes for mining Ethereum. Mining hardware must have enough memory capacity to store it. The dataset grows at a rate of approximately 1GB every two years for Ether, though other coins may have different growth rates. Four-gigabyte devices will have been completely unusable by the end of 2020, while 6GB-cards are likely to have been depreciated by 2024. Online calculators can help evaluate the exact time schedule.

The central processing unit can be as cheap as necessary, as it has no relevance to GPU mining. Multiple-GPU setups are likely to require risers, an adapter to allow GPUs to be connected to the motherboard. The mining rig case should be open and wide enough to allow air circulation.

In terms of the operating system, Windows and Linux are both valid options, though Linux may require more command-line interactions to set up. It’s crucial to optimize the GPUs in terms of clock speed, power usage and memory timings to achieve the figures outlined earlier, but a full roundup is outside of the scope of this guide.

The most straightforward way to mine ETH is by joining one of many Ethereum mining pools like SparkPool, Nanopool, F2Pool and many others. These allow miners to have a constant stream of income instead of a random chance of finding a whole block once in a while. Popular mining software includes Ethminer, Claymore and Phoenix. It may be worth testing each one to see which is faster for your specific configuration.

Finally, the devices should be regularly maintained, cleaned and dusted to keep the hardware in good standing. There are other details involved with setting up a successful mining farm, many of which are jealously guarded as trade secrets. This guide is not meant to be entirely comprehensive, but if you are serious about mining, you should now have a strong knowledge base to conduct further research.

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 76833 more Info on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 21920 more Info on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 51096 additional Information on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 52838 additional Information on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 39797 more Info on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here to that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on on that Topic: x.superex.com/academys/beginner/2814/ […]